The first question that will most likely pop into your head after reading the title is, “well, what is your core?”. Or, it could be “isn’t your core just your abs?” The answers to these questions are pivotal in understanding my concept of training the baseball core.

I personally think some of the biggest issues I see in young baseball players are:

- lack of core control

- lack of core strength

- lack of core stability

If you have a problem in all three areas of control, strength, and stability, then you are asking for issues. Every athletic movement initiates from the hips, and energy is translated through the core. If you lack core control strength or stability, you can see that some energy created will be lost as heat due to the inability to properly transfer force to the limbs. Before getting into each concept one-by-one we should answer the question, “well, what is your core?”

Think about the core of an apple. Where will you find it? The middle of the apple.

Now, think about the core of the body. Where will you find it? In the middle!

Your trunk and your core are synonymous. The core musculature is what surrounds the spine, and it’s main job is to stabilize the spine during movement in all 3 planes of motion.

Now that we understand that the core is the middle of the body, otherwise known as the trunk, let’s go over the sequencing of core training for baseball players.

Core Control

Most of the baseball population that I train is dumped into an anterior pelvic tilt, which is totally common to a certain degree, as long as it isn’t severe.

The part that I really care about is the ability to move the pelvis to get into a neutral position. Surprisingly, a lot of athletes struggle with this concept of moving the pelvis. This can become an issue when we start to load the body and the athlete is unable to put the pelvis into a neutral position when performing an exercise.

When looking at the upper back (a.k.a. the thoracic spine), there is a mix of kids who have a flat T-spine and an excessively rounded T-spine. Again, this is fine, but it will dictate the rest of the movements that occur around the spine and along the rib cage.

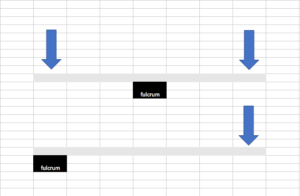

When performing evaluations, the most simple test to see where an athlete’s core control is at is with the Active Straight Leg Lowering. The analogy that I use with athletes is a seesaw.

In a seesaw, the fulcrum lies in the middle of the lever. When force is applied more on one end than the other, this results in the lever moving down towards that side along the fulcrum.

When performing the Active Straight Leg Lowering test, the fulcrum is now moved all the way to one end of the lever. As the legs begin to move slowly towards the ground, the fulcrum has to work twice as hard to resist it from “breaking”. This break from the ground is when the pelvis is no longer able to create internal force that is greater than the external force of gravity (this concept blends into core strength).

However, let’s keep in mind that this movement is only in one plane of motion, and that gravity has a huge effect on core control. Laying down on your back is going to be less demanding than in the standing position.

One way to see an athlete’s core control is to perform a bodyweight squat. Does the spine dump forward during the descent? Does it dump forward during the ascent?

To make the squat more difficult, we perform the Overhead Squat Test, made popular by the Functional Movement Screen (FMS). The athlete should be able to control the squat pattern with the arms remaining over the head and the elbows in line with the ears. Any compensation of movement results in a lack of core control and core strength.

Another way to see an athlete’s core control in a different position in relation to gravity is a plank. What do they use to create stability? What happens when we take away a point of stability? Are they able to put the pelvis into a neutral position during a plank?

The main concept from having good “core control” is setting the pelvis into neutral and setting the upper spine into neutral. Once we can create a stable spine, then the limbs will be able to transfer more force. More often than not, athletes are not the greatest at setting the pelvis into neutral during any sort of movement (pushup, bear crawl, chin up…literally anything).

The biggest takeaway is having the ability to create movement from the hips and the ribs/upper back, as well as having the ability to resist movement at the same time.

![]()

Core Strength

We can build core strength simultaneously with creating core control (in some cases). If an athlete lacks core control, which also means they won’t have great core strength either, I like to keep it simple with static holds.

Any plank or bird dog variation can be used here. In the sport of baseball, the core only fires for a short amount of time since throwing and swinging occur in just seconds. When starting off a beginner athlete with some core work, I recommend using static holds of no longer than 5 seconds. Here’s an example to progressively overload static holds:

- Week 1: 5x5s

- Week 2: 6x5s

- Week 3: 7x5s

- Week 4: 8x5s

In the evaluations that I perform, we use the “3-Minute Plank Test” created by Infiniti Performance Co-Owner Russ Taveras. For the first minute, we have the athlete hold a normal plank. Are they able to maintain a rigid spine for a minute straight? You’d be surprised that there is a good handful of athletes who struggle to keep the perfect plank in a minute.

Now, an athlete can show true core control of setting the pelvis and rib cage into neutral but lacks the strength to keep it there under load. THIS is how you build true core strength: apply load to the body when the core is in neutral, and then see what breaks down and when.

The variations for creating core strength are endless, and these exercises can either be static or dynamic in nature. To make matters simple, here’s a list to use:

- Anti-Rotation and Rotation (side plank variations, diagonal and horizontal chops)

- Anti-Extension (plank variations)

- Anti-Flexion (front-loaded carries)

- Anti-Lateral Flexion (side-loaded carries, diagonal lifts)

Once the athlete understands how to set the core into neutral, then we can get fancy with how we load the body. However, it is important to not skip step number 1, which is creating core control first.

To build core strength, you can kill two birds with one stone when you perform a lower body exercise with the load being placed in front of the body. Some of these variations include:

- Front Loaded Lunges/Split Squats

- Off-Set Loaded Lunges/Split Squats

The fun exercises are when we perform rotational core variations, since rotation is where the performance happens in baseball.

With every medicine ball drill that my athletes do, who have prior core control and proper core strength to perform correctly, I mainly look for the hips and the pelvis to initiate the movement.

The one cue that usually works for me and most of the athletes I work with is “punching your pocket to the wall”, which allows for the hips to fully rotate through to finish the movement.

Core Stability

As I mentioned previously, gravity has a great effect on our core control. When we are down on the ground performing a plank variation, the amount of recruitment will be far less than in the standing position.

As we get closer to the competitive season, we want most of our baseball athletes to be able to create proper core engagement in the standing position, otherwise known as “ground-based” core training. Here is a simple position progression you can follow to create strength and stability:

- Half-Kneeling

- Tall-Kneeling

- Wide Bilateral Stance

- Narrow Bilateral Stance

- Split Stance

- Single Leg

While ground-based movements are going to be difficult, the biggest movement pattern that I see a lot of athletes struggle with is the crawling pattern. When performing a proper crawl, our base of support dynamically changes from 4-points (both hands and feet) to 2-points (opposite hand and foot). When performing a crawl correctly, it is pretty damn hard to control our pelvis in multiple planes of motion and allow it to stay in neutral.

The biggest external feedback you can give to an athlete is putting a cone on their lower back during a crawl. You’ll most likely see the cone keep falling off towards one side of the body. In this case, it shows that resisting rotation on one side (or really just simply rotating against it) will be a lot harder on one side of the body, since the pelvis is so used to creating movement towards one side of the body time and time again.

Reverse Crawls

The ultimate goal for the baseball athlete is to have excellent core control and a strong, stable spine in different positions. Once we understand how to create efficient movement and initiate from the hips, we’ll be swinging harder and throwing faster in no time.